Unless you’ve been living under a rock, no doubt you’ve heard vague mutterings about inflammation and its negative health effects. But what is inflammation? And should we be concerned? In the next few paragraphs, I hope to give a brief overview of what chronic inflammation is and suggest some diet and lifestyle changes that may help to counteract it.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, no doubt you’ve heard vague mutterings about inflammation and its negative health effects. But what is inflammation? And should we be concerned? In the next few paragraphs, I hope to give a brief overview of what chronic inflammation is and suggest some diet and lifestyle changes that may help to counteract it.

First, I want to say all inflammation is not bad. Acute inflammation occurs as a response to some sort of attack on our immune system, like an infection or cut. This is a short-term, protective process that keeps us healthy by fighting off the offending microorganism or healing the damaged tissue. Typically, this process occurs over a few hours to a few days. The type of disease-promoting inflammation you’ve no doubt heard of is chronic inflammation. This is a low-grade form of inflammation that persists long-term—like for months or years. Often there is no obvious trigger, although there are many lifestyle choices that have been associated with it. This chronic inflammation, or “inflammaging,” is the basis of a prominent theory of how we age. The idea is the products of inflammation cause tissue damage, eventually leading to organ damage and chronic disease. (1) Diseases associated with chronic inflammation include heart disease, diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease, which are some of the most widespread, costly, and deadly diseases of our lifetime. (2) One way we may be able to prevent or reduce them is to target inflammation as a root cause.

When we talk about disease risk, there are always risk factors that you can change (called modifiable) and those that you cannot change, called non-modifiable. Non-modifiable risk factors are things like your age, ethnicity, or family history of disease. Let’s face it—some of us got the short end of the stick when it comes to these (myself included). However, there are many modifiable risk factors that we can change. And one of the big modifiable risk factors associated with chronic inflammatory diseases is—you guessed it—diet. So, how can what you put in your mouth help combat this? Read on to learn my top 10 tips for eating an anti-inflammatory diet.

- Work towards a healthy weight. Those who fall into an overweight or obese category have been found to have higher rates of inflammation and are at a higher risk for many of the diseases associated with it. (3) Following some of the suggestions below can help you work towards this goal.

- Cut back on calories. It has long been observed that those who eat a lower calorie diet long term live longer and have fewer diseases. One of the ideas behind this is they have reduced chronic inflammation. It must be said that many of these people were eating severely restricted calorie diets—like 30-40% reduction of total calories. What I would suggest is more mild (like 10% of total calorie intake) as severe restrictions can cause health concerns. (4) Dr. Valter Longo, whose research on longevity is fascinating, recommends in his new book reducing calories as simple sugars and protein. To replace these, he suggests turning to complex carbohydrates and healthy fats. (5)

- Cut the sugar. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again; all the added sugar in our diet is not doing us any health favors. There is evidence that sugar plays a role in inflammatory diseases. (6, 7) As an exercise in mindfulness, I challenge you to eliminate anything that has added sugar (or artificial sweeteners for that matter) for one week. Read food labels and don’t choose anything that has the word sugar or one of its many pseudonyms. This exercise will open your mind to the unsettling fact that sugar is added to soooo many things and may help you choose an alternative without it.

- Keep your carbohydrates complex. Sources of carbohydrates should be mostly non-starchy vegetables like chickpeas, lentils, beans, and 100% whole grain bread and rice. I recommend focusing on veggies and legumes even more than the grains and rice. The flip side of this is to eat fewer simple carbohydrates, which includes sugar, refined grains, rice, and starchy vegetables like potatoes and corn.

- Focus on healthy fats. Use olive oil as your main oil in cooking and salad dressings and eat 1 ounce of nuts like almonds or walnuts each day. Eat fish according to the guidelines below. Limit other vegetable oils like soybean and corn oils which are often found in pre-made packaged food. (5)

- Eat fish and seafood. Ideally 2-3 servings per week. Best choices are salmon, anchovies, sardines, cod, sea bream, trout, clams, and shrimp. (5) These are higher in anti-inflammatory omega-3 fats and are eaten by many populations who have the longest lifespan. Keep fish with a high mercury content (halibut, tuna, swordfish, mackerel) to no more than one serving per week.

- Go (semi) vegetarian. Research has suggested that a diet high in animal protein is associated with inflammation. (8) There is also evidence that vegetarians have reduced inflammation and heart disease. (9) If this is a big step for you, start by cutting out meat at lunch or one day each week and work your way up from there.

- Eat your F and V’s. Fruits and veggies, that is. These are high in antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals. Aim to eat colorful fruits and vegetables and try to get a variety each week. Those particularly high in antioxidants, which may reduce inflammation, are citrus fruits, kiwi, strawberries, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, spinach, carrots, and sweet bell peppers.

- Pamper your gut bacteria. A microbiome that is out of whack has been linked to inflammation and inflammatory diseases. For tips on keeping yours in tip-top shape, check out part 1 and part 2 of our post on gut health.

- Pump the brakes on alcohol. Alcohol is known to increase inflammation, so keep your intake to recommended guidelines: no more than one drink daily for women and two a day for men. Also, consider what else is in the drink, like added sugar. Red wine seems to be a safe and delicious drink when consumed in moderation.

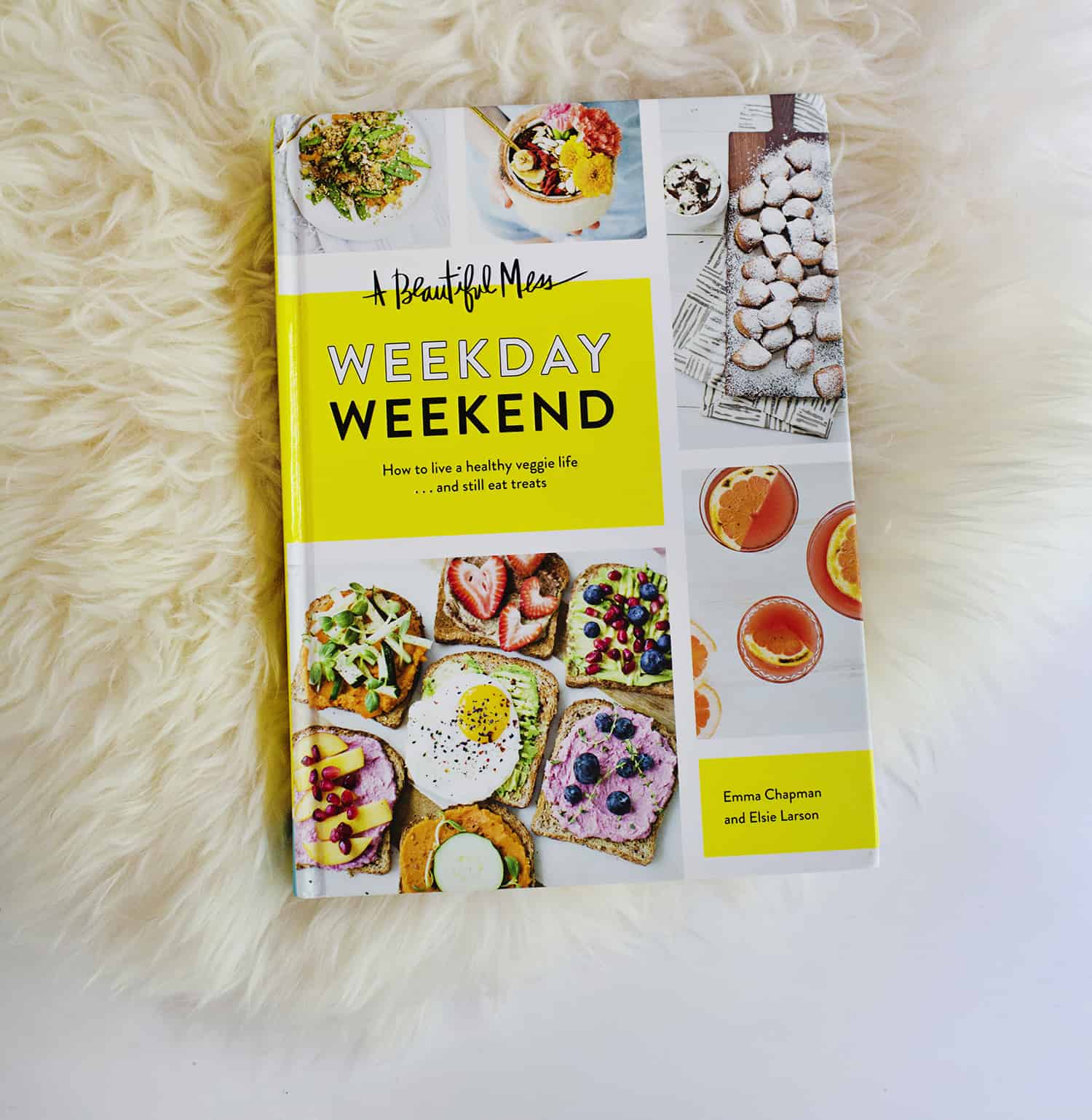

After working on this post, it dawned on me that the above suggestions are things I would recommend as an all-around healthy diet. Makes sense when you think about inflammation being a common denominator of many preventable diseases, right? I also can’t go without saying there are many similarities between an anti-inflammatory diet and the weekday rules from Elsie + Emma’s cookbook, Weekday Weekend. How cool is that? If you’re looking for more details or recipes and you haven’t checked it out, I would definitely suggest getting a copy of your own! – Lindsey

After working on this post, it dawned on me that the above suggestions are things I would recommend as an all-around healthy diet. Makes sense when you think about inflammation being a common denominator of many preventable diseases, right? I also can’t go without saying there are many similarities between an anti-inflammatory diet and the weekday rules from Elsie + Emma’s cookbook, Weekday Weekend. How cool is that? If you’re looking for more details or recipes and you haven’t checked it out, I would definitely suggest getting a copy of your own! – Lindsey

A note from Sarah:

Slam dunk, Lindsey. I wanted to take a brief sec to review non-diet ways to fight chronic inflammation. It’s important to remember that stress is a prime driver of chronic inflammation so try to find ways to fight stress—exercise, meditation, yoga, plenty of sleep … really anything that helps give your brain a “time out” every once in a while is always advisable. Check out my last post on adaptogens which also boast many anti-inflammatory and stress fighting properties. Breathe deeply, take breaks, and make time for self-care—however that may look.

5 Comments

Thank you for the tips! I actually follow most of the tips already! 🙂

Charmaine Ng | Architecture & Lifestyle Blog

http://charmainenyw.com

Thank you so much for this post! I have endometriosis and an anti inflammation diet has been so helpful in managing the pain that goes along with it. These are great tips – thank you!

Such a lovely post, thanks all!

xo

Phyllis

http://desgeulasse.com/

A really informative post, I already do most of the above as a healthy lifestyle choice but there is still room for improvement

With Elizabeth H

Thanks for the advices hope that I’m not gonna be having a hard time doing it. I love Carbs but I need to be healthy as well.